Starbucks: The Modern Globalization Imperative

Thursday, October 11, 2012 at 5:10PM

Thursday, October 11, 2012 at 5:10PM Be very local and very global

Lately Starbucks has been faltering. It expanded too fast, many say And its brand has stumbled. It lacks focus, and some consumers have rejected it outright. They aren't clear any more about whether the company is about coffee, or music, or adult shakes such as Frappucinos. And some doubt the company's reputation as being eco-friendly, considering that as just corporate posturing to mask the high price of their coffee. (See Bryant Simon's "Everything but the Coffee: Learning about America from Starbucks" for an interesting analysis.)

Starbucks, ultimately, is more than coffee. "Starbucks ... sells experience." (Starbucks Global Advisory Council meets in Dubai, AMEInfo.com, 4/30/2006). You don't update Starbucks by updating the coffee. You update the brand values delivered in the in-store experience. It's long past time for Starbucks to ramp up its local relevance - city by city, country by country -- while also exploiting its uniquely global resources and abilities.

Emotional and cultural intelligence

To get at how local markets such as China, Germany, and France view Starbucks requires emotional intelligence and cultural sensitivity.

Partnerships help moderate market entry risk. Starbucks partnered with Alshaya Group to help them grow their Middle East and Turkey markets. KarstadtOuelle AG assisted Starbucks' entry into Germany. KarstadtOuelle's 82 percent interest in the German venture was later bought back by Starbucks after the company learned what it needed from German consumers. Similarly, Starbucks just announced that it is buying back interest in its French market from Spanish partner Sigla, S.A. (Sigla will retain its Starbucks portfolio in Spain and Portugal.) The pattern: Risk a little in a co-venture, and learn from your partners' internal (often implicit) knowledge of, and experiments in, the target market.

Some global CEM strategy basics

My own CEM framework turns Michael Porter's five forces work inside out by shifting corporate strategy from a sector orientation to a customer ecosystem perspective. One consequence of this approach is that the strategist must build his work on what drives consumer choice and behavior. International strategy requires that the strategist analyze systems of meaning and value that dominate a consumer's world view.

To do this (as Sidney Levy and Phil Kotler implied as long ago as 1969), the strategist must understand how a company advances the conversation about the symbolic characteristics of a market's world of meaning. Customers live in a world of symbols and signs, and if a company wants to be one of those symbols or signs, it has to deeply understand and work within that world. After all, a company does not define its brand alone. The brand is granted meaning by its customers.

Tactically, companies must start with measuring customer behaviors and attitudes at touch points to see how experiences at these touch points create or destroy passion for the brand. A smart company innovates these touch points by exploiting the company's unique resources to design touch points, or to add them, or even take some away, to create competitive positioning.

Fundamentally, the multinational must answer two broad questions: how do cultural values, signs and symbols influence touch point design from region to region? And, how can the product, service, and touch point experience create defensible value?

The backstory

Starbucks is a high-end coffee retailer and product brand originating from the Pacific Northwest of the United States. It has grown to more than 15,000 stores globally in just over 30 years of operations.

It sourced coffees internationally and blended them to turn a commodity - coffee beans - into something difficult for competitors to copy.

Starbucks, in fact, has created an entirely new vocabulary about coffee which, although it might seem Italian with terms like grande latte, is a semantic space all its own.

Posted under Creative Commons License. Copyright by Nicki Dugan.

Posted under Creative Commons License. Copyright by Nicki Dugan.

Starbucks marketers have been developing this language since the 1980s about coffee beans, evoking a mythical world filtered with the domestic U.S. view of consumption and foreign lands. "Although Starbucks proudly serves its coffee around the world, the company's sense of geography is refracted through a commodified Western lens... [One] journalist carped that unsuspecting consumers must choose from 'beans from countries that college graduates cannot find on a map'." (Charlene Elliott, Consuming Caffeine: The Discourse of Starbucks and Coffee, Consumption, Markets & Culture, Volume 4, Number 1.) And the language was filled with Western-biased terms: "Orientalism pivots on the notion of the 'mysterious East'... and often portrays the foreign as primitive," says Elliot. "Coffees are 'magical', 'intriguing', 'fleeting', 'elusive', 'nearly indescribable' (i.e., mysterious), and 'wild' and 'earthy' (i.e., primitive). And as with Orientalism, these descriptors exist to be observed and consumed by the West."

Indeed, Starbucks' ability to create an exotic, Orientalist world in the minds of educated domestic U.S. consumers relied upon sourcing coffees from far-flung - mysterious - parts of the planet. The mystery is elemental to the coffee experience. Not surprising, then, that Starbucks sourced beans from non-Chinese sources when it entered China (Ibid.).

This exoticism - a key part of creating the Starbucks brand - needed to be protected. Could a local coffee shop actually source, roast, and blend consistently beans from the Pacific Rim and Africa to create a unique, trademarked offering? "A commodity of Yemen is ground with a commodity of Indonesia to create a non-commodity product: Arabian Mocha JavaTM. Similarly, the beans of East Africa mix with those of Latin America to become Siren's Note BlendTM." (Ibid.)

Exporting Brand Values

When faced with Europe, Starbucks faced a unique challenge for its exotic beans and language: What Americans find exotic doesn't translate well to Europe. Europe has been the trading center for some of the world's most exotic goods from far-flung locales for centuries. Angola is just not exotic in Europe. And European familiarity with coffee preparations - even specific Italian styles of coffee - make the faux-Italian language of Starbucks' main menu confusing, even laughable. Even the "third space" concept that Starbucks innovated in the United States is what France has enjoyed enthusiastically since World War II - thirty years before Starbucks was more than a glimmer of a brand concept.

To get a hint of how Starbucks' unique set of brand values is being into something relevant and uniquely defensible in the French context, something I've been tracking for several years now.

The initial positioning echoed the US approach: a coffee shop/restaurant offering a "branded Starbucks experience" (even today near the entrance to rue Mouffetard at rue de Bazeilles, for example, remains a classic American experience). Over time, I noticed Starbucks employees on the sidewalk educating passersby in how to "create your own coffee", attempting to appeal to a classically French sense of artistry and creativity - perhaps as a form of self-expression. I saw the company's positioning shift. (You can see the France Starbucks site here: http://www.starbucks.fr. It has memorialized the positioning shift in its language about legacy, personalization, and values.)

Recently, the Starbucks strategy in Paris seems to be promoting purchases of its coffees as an endorsement - and economic support -- of the foreign producers of the coffee beans that capture the unique characteristics of the soil and light. This blends the classic French concept of métier (pride in one's skill as an artisan or professional), terroir (land-specific produce), with a "green and sustainable" brand promise.

Of the brand values Starbucks has established over the years, in France it is reinforcing the few which make it powerfully relevant to French consumers: Métier, terroir, sustainability. In fact, since Howard Schultz (once CEO and then Chairman of the company) regained the position of CEO in January 2008, the company has been moving rapidly towards an eco-friendly image.

Positioning is only meaningful in business terms if it can be defended. And Starbucks can defend itself well. It has committed to specific recycling and energy-efficiency goals on an aggressive timetable. Starbucks just introduced double-flush toilets in Australia. "Studies of dual flush toilets show that using a dual flush system as opposed to a conventional one can reduce water consumption by up to 67%," according to ServiceMagic.com. "[People] come out of those coffeehouses and that's what they're talking about - the dual-flush toilets," according to Starbucks Corporate Architect Tony Gale (Starbucks brews global green-building plan, renovates Seattle shop, by Sarah Van Schagen, 6/30/2009, Grist). And they partnered with GE to create a new low-cost light. And Starbucks is not going to let you forget its commitments: "Starbucks is adding explanatory signage through [its] stores to highlight the sustainable elements." [Ibid.]

Outlocal the locals?

Sustainability and eco-friendliness is a huge differentiator for Starbucks when its chief competition is a local mom-and-pop coffee shop which can never have the accumulated impact of a multinational corporation.

And yet local owners don't have Starbucks' big-corporation, multinational baggage. Ethiopia accused Starbucks in 2007 of "coffee colonialism" (Simon, page 17), and the National Labor Relations Board (US) discovered consistent violations of the National Labor Relations Act in some US-based stores (Huffington Post). While the company has been rewarded with international ethical management recognition (Covalence Ethical Ranking, 2006, places Starbucks #3 globally compared to all other companies), Starbucks' organic and fair trade practices have been a source of ridicule by some who believe that it has not gone far enough. Many consumers may have the impression from Starbucks signage that it treats its coffee purveyors fairly, but its use of fair trade coffee is only a tiny fraction of all the coffee it sources.

Starbucks' brand for many of its former core audiences has been sullied.

Two strategies emerge. If you determine that you're better off being local, be as local as you can be, by leveraging uniquely local resources. And second, hide your global brand as much as possible. Starbucks has embraced them both.

The company recently launched a series of new stores and revamped existing ones, that barely hint at their association with Starbucks. They simultaneously create a distinctive, well-calibrated local offering. And to differentiate themselves from local competition, customers can also enjoy difficult-to-copy coffee products in a pleasing space designed by some of the most sophisticated architects in the world.

Sara Kiesler reports in SeattlePi.com that three rebranded stores in Seattle, called "un-Starbucks", or "stealth stores, have a local focus, and even break from Starbucks' well-tuned processes, products, equipment and training." "In order to have relevance, I said, how about we name it after the street," said D. Major Cohen, senior project design manager for the 15th Avenue Coffee and Tea, a wholly-owned Starbucks shop. Using French presses and small-batch brewers, the store also features whole-leaf teas and "no Frappucinos whatsoever," says Kiesler. Even the beans have been rebranded with the local store name (Seattle Times).

You can still get a hard-to-copy Guatamalan Antigua blend. That's important because competitors cannot offer the same level of exoticism, which remains hard to copy, but you can also get Seattle-specific goodies, such as smoked salmon, local entertainment, and sandwiches from a local bakery with an excellent reputation. You can even get wine and cheese in the afternoon. Cohen says that it's all about giving the neighborhood what it wants.

Plus, 15th Avenue Coffee and Tea is eco-friendly.

You can bet that 15th Avenue Coffee and Tea is still known as a Starbucks shop, even if it's only via word-of-mouth. But consider what is surely in the back of the consumer's mind: only Starbucks has the size needed to make a huge impact on the environment. And Starbucks isn't really trying to ram its brand down the fatigued, cynical consumers throat. The company seems to be saying that its branding is not as important as its eco-friendly commitments and desire to be your locally-focused coffee shop.

Will global consumers buy it? One thing's for sure: Starbucks has made an effort to change the conversation. And both Levy and Kotler would agree that it cannot succeed unless Starbucks advances the conversation about the symbolic characteristics of how we view the company, the brand, the store - and what our money is used for beyond just buying a cup of coffee.

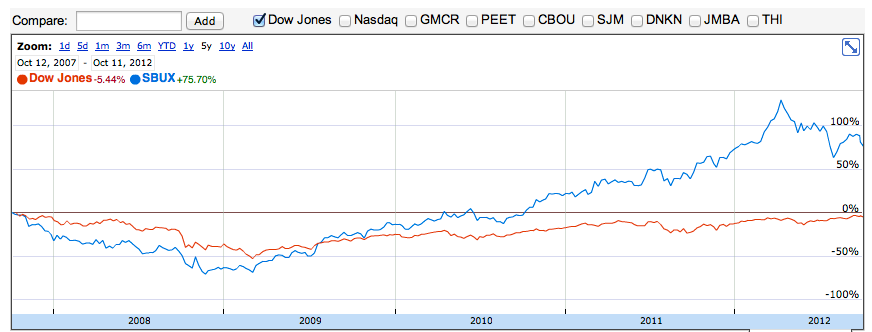

After a period of stress, Starbucks' former CEO returned to the company in 2008. Some wondered whether he had what it would take to reinvigorate the brand, particularly as the economic crisis worsened.

Whether or not the brand is improving, the company is doing well since Mr. Schultz returned, outperforming the market consistently. Take a look. What's helping?

Reader Comments